Release date: January 31, 2025

The last of a generation

My uncle passed away earlier this month. He wasn’t really my uncle, instead he was my mom’s cousin, but, since Mom was an only child, and she and John had grown up together as children, calling him “Uncle John” was a no-brainer.

As a little girl, I remember our two families spending time together. Not a lot of time, but the occasional holiday or weekend away. Enough time to feel the tug of kinship and belonging. But my relationship with John really took off after my parents had passed away, leaving me searching for “my people”, whatever that meant.

John and I would sit at his big oak dining table – a table that had lived in my maternal great grandparent’s farmhouse before relocating to John’s – and talk family. As the designated kinkeeper, I knew the facts, but John…he remembered all the stories.

And he was generous in sharing them.

When my grandpa came home from the Navy in 1945, John was at the welcome home party held at the family farm.

“We spent that whole week getting ready,” I remember him telling me. “We butchered two hogs and more chickens than I could count. And then Grandma and the other women set about making sausage. I can still see it hanging in the old smokehouse.”

He knew the scandal around Auntie Myrtle’s marriage to Uncle Maurice, the heartbreak of his father’s long widowhood, and the story behind every family marker at the local cemetery.

And it wasn’t just stories from our shared Semerau family that John remembered. He’d known my dad and his family since childhood, as well. Both sides, all sides, would often gather together for family celebrations, milestones and funerals. So many of the photos I inherited from John, photos we’d looked at together, showed me who all “my people” were.

I’ll be forever grateful for that.

Before John passed away, he’d gathered up all the old family photos and documents – tax and land records, funeral home books, military discharge papers and country school report cards – which had been handed down to him over the years, and set them aside for me. At 91, John was the last of his generation, the bridge between ancestors and descendants, and it was a responsibility he took seriously.

I do, too.

Blessed are they who mourn, for they shall be fed

Like all the women in my Semerau family, John’s mom, Leona, was a member of the kitchen crew at her local church. These ladies were in charge of preparing and serving what Lutheran Minnesotans like to call the “funeral food”, a distinct menu of simple comfort foods which, honestly, are rarely seen outside a church basement.

Among the traditional offerings are two of my favorites, Marshmallow Fruit Salad and the Mother of all funeral foods, a dish which goes by many names, but is most often referred to as Funeral Spread or Funeral Home Salad.

Neither of these funeral foods really requires a recipe as they’re embedded in our DNA, and also dead simple. But, for those non-Minnesotans or others who prefer clear directions, I offer the following:

Marshmallow Fruit Salad

Ingredients:

2 15-oz cans of fruit cocktail, drained

1 8-oz container of Cool Whip

2 cups mini marshmallows

2 sliced bananas

Instructions:

Drain the fruit cocktail and put in large mixing bowl

Fold in the cool whip and marshmallows then add sliced bananas.

Cover and refrigerate until ready to serve.

Bologna Funeral Spread AKA Funeral Home Salad

Ingredients:

½ cup ground or chopped bologna

1 hard-cooked egg, chopped

2 Tbs chopped sweet pickle

1 Tbs chopped onion

4 Tbs mayonnaise

1/4 tsp salt

Instructions:

Mix well. Spread on buttered dinner rolls and serve

Other foods served in Lutheran church basements where the recently-deceased are honored and remembered include lime Jello® with shredded carrots, homemade pickles and an assortment of bars – Scotcheroos, Rhubarb Bars, Seven Layer Bars even Lemon Bars – but very rarely cookies.

Bars, it turns out – some people call them bar cookies to differentiate them from the other type of bars so popular in my home state – are another distinctly Minnesota, or at least Midwestern, thing, as Minnesota journalist Joy Summers pointed out in her 2023 article titled, “No Time for Cookies: Bars are the Midwestern Way to Say, ‘I Love You!”

Those not from here might not pick up on the subtle, tonal differences of the way we say "bars." But a Midwesterner knows that when the tenor is deep and the inflection lands on the "b," that we're talking about a place where grown folks drink. But a softer-said "bars" — where the "a" bleeds into "ah" and the "r" is quick and sharp, but the "s" lingers like we do on a doorstep when we drop them off — is what we bake when we want to show someone that we care.

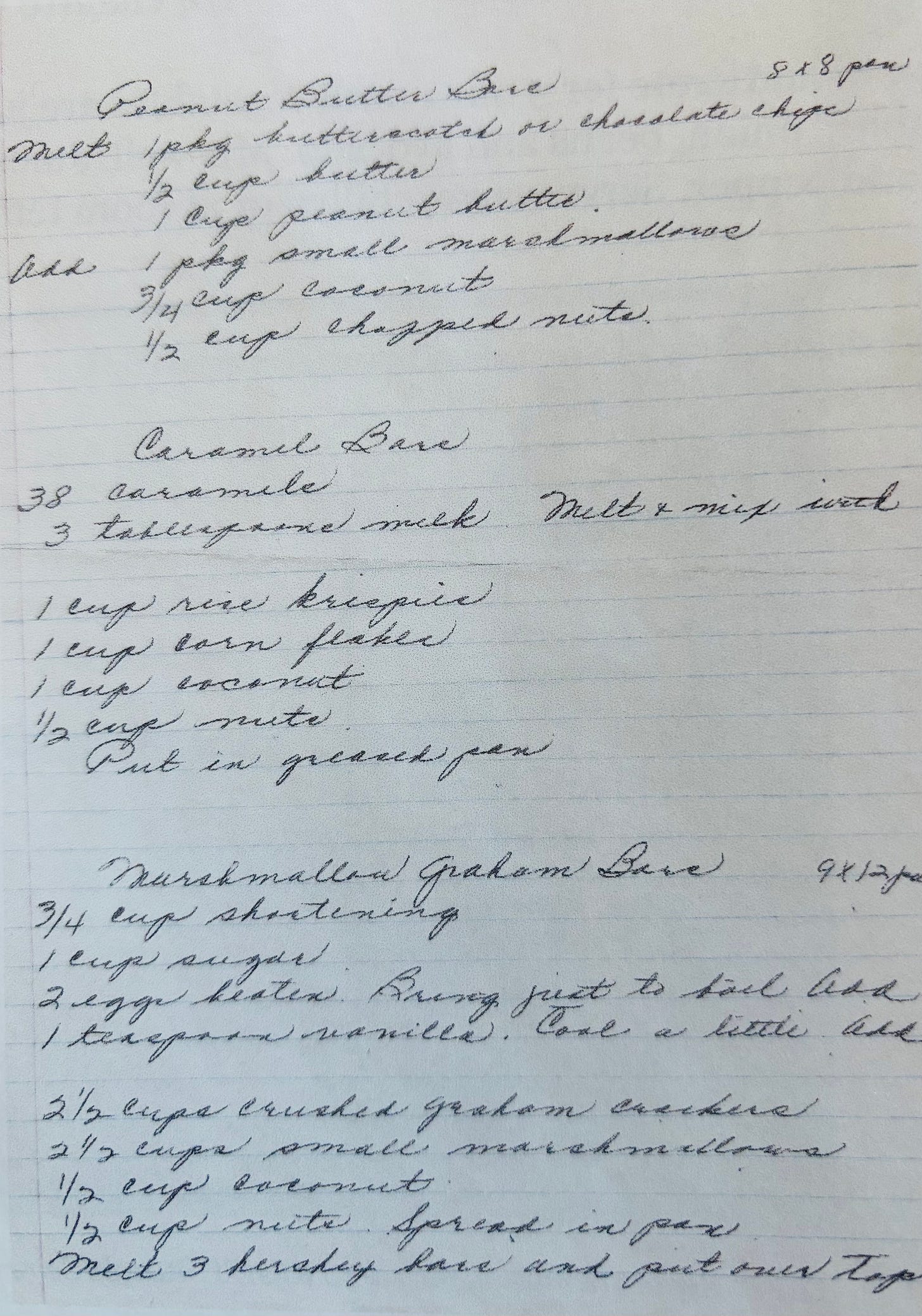

Semerau Family No-Bake Bar Recipes

John’s jelly jars

After the funeral, the internment and the luncheon, we went back to John’s house. We sat around and reminisced, shared stories, reconnected after years of life making family get-togethers few and far between.

We joked that the only time we saw each other was at a funeral, and then, as happens, vowed to do better.

At some point, I went to the kitchen to get something to drink, and when I opened the cabinet door, memories fell out.

Well, not memories exactly. Jelly jars.

John was a successful and creative architect and had always lived in the most extraordinary houses — especially when compared to the simple home I grew up in. Where my parents favored braided wool rugs and Early American furniture Dad had handcrafted in his wood shop, John was all about big, bold colors, floor-to-ceiling walls of shiny aluminum and glass, and shag carpeting so thick and deep I’d curl my little toes into it until the cramps forced me to cry ‘uncle’.

Even before I knew what ‘sophisticated’, meant I knew it described John.

So, imagine my surprise, the disconnect, when I realized John used old jelly jars as drinking glasses!

He filled them with juice for breakfast, and milk at meals. He kept one filled with water on the end table next to his favorite chair, and another in the bathroom. John’s house was filled with old jelly jars.

I remember asking Grandma about it one time, and she simply smiled and called it ‘John’s quirk’.

John was the only person I ever knew who drank out of jelly jars. But, it turns out, it wasn’t so much a quirk as it was a nod to nostalgia. Maybe even a way to hold on to a piece of our family’s culinary history.

Before 1916, when someone needed to buy groceries they’d bring a shopping list to the local market, and the grocer would do the shopping for them, gathering the requested items from behind their large counter, and even packaging the items for the journey home. But, all that changed when Piggly Wiggly came to town. America’s first self-serve grocery store allowed customers to pick out the items they wanted on their own, and suddenly the way a product looked made a huge difference.

Welcome to the age of food marketing!

Among the folks who were paying attention to this new trend were commercial glassmakers. They’d long been making glass containers to hold jams and jelly, and knew those containers were often saved and used as drinking glasses. To add shelf appeal, the glassmakers started adding decorative details to their jelly jars, and making them in sizes and shapes more easily used in their afterlife.

Consumers loved the idea and drinking out of jelly jars quickly became all the rage.

John was born in 1933, about the time jelly jar glasses were coming into style — including ones decorated with cartoon characters and advertised for on the Howdy Doody Show. It could be he grew up drinking out of them, and carried that tradition into adulthood. Maybe he was ahead of the curve and recognized the sustainability and environmental benefits of reusing and repurposing glass containers. Or maybe he simply liked the way a jelly jar felt in his hand as he sipped his morning juice.

I never bothered to ask. But I sure wish I had!

Copyright 2025 Lori Olson White

Your turn and your culinary traditions

Food as Comfort – What dishes are most commonly prepared or shared at funerals in your family or community? Are there specific comfort foods that always appear?

A Dish with Meaning – Is there a particular food or recipe that has special significance when mourning a loved one? Where did the tradition originate, and has it changed over time?

Who Brings the Food? – In your family or community, who takes on the responsibility of preparing and bringing food after a death? Is it family, close friends, or a larger community effort?

The Role of Gathering – How does food play a role in bringing people together after a loss? Are meals shared at a specific location, such as a church hall, someone’s home, or a graveside picnic?

Unspoken Rules and Rituals – Are there specific etiquette or customs around funeral food? For example, are certain dishes expected, or are there rules about who serves or receives the food?

Regional or Cultural Influences – How do geography and cultural background shape funeral food traditions in your family? Have these traditions changed due to migration, modern influences, or generational shifts?

A Recipe of Remembrance – Is there a recipe that reminds you of a loved one who has passed? What memories does it bring back, and how does preparing or eating it help keep their memory alive?

Evolving Traditions – Have you noticed any changes in funeral food traditions over time? Are younger generations maintaining them, adapting them, or replacing them with new customs?

On February 13, 2025, I will be presenting a family story close to my heart in a free program titled, Howard and Elvira: Love and the German Chocolate Cake, and I’d love to have you join me! This program will be held exclusively online and everyone is welcome. Link details will be emailed to you after registration. See you there!

Please hit the “like” button if you enjoyed this newsletter — it’s a little thing you can do to support my work!

Culinary History is Family History is reader-supported. When you buy through links on our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

I grew up at a time and place where it was considered that children should be ‘protected’ from death and funerals. I didn't go to a funeral until I was well into my adulthood. My grandparents were there one minute and gone the next with no in-between transition. Something I have always felt resentful about but it is just how things were done in those days.. Food does play a part here … but not in quite such an extensive way ... just finger food ... a sandwich or two, sausage roll, piece of cake ... These days the focus is on a celebration of life and the food after the service draws people together to swap stories about the deceased over a cup of tea or coffee and pay their respect to those who have most closely suffered the loss.

I thoroughly enjoyed this piece, Lori. It’s fascinating to consider the many traditions of sharing food following a funeral. As you know, I wrote a little about what we ate at my cousin’s funeral in my latest Substack post (link below ICYMI). It’s so interesting to read these recipes you share for bar cookies and marshmallow fruit salad. In our Jewish tradition, there’s often a mourning period that lasts a week. Easy-to-eat and serve food that promotes comfort and storytelling is really the central point. At a Jewish gathering, bagels and lox, salad and snack platters, and cookies and cakes fill the bill. Sometimes they’re ordered from a restaurant, or volunteers from the community’s provide them. My cousin, as I wrote, had a special request. Here’s what I wrote: https://open.substack.com/pub/ruthtalksfood/p/a-funeral-feast?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web